TOP OF THE BEAT TACTICS

November 1, 2001, by Bob Merrick

Sailing World

As you approach the weather mark in a crowd and sail in a progressively smaller cone of water, finding a clear lane becomes more difficult. It’s important to know what boats are ahead of you, anticipate their next moves, and react accordingly. Doing so will allow you to sail in clear air for as long as possible while sticking close to your overall leg strategy. Here are tactics for dealing with situations you may encounter at the top of the beat.

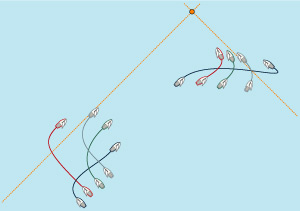

In both of these situations the fourth-place boat (darkest line) can make up ground by tacking early (left) or overstanding slightly (right).

Just behind, approaching a long layline

You’re just behind a pack of boats as you approach a long port or starboard layline. In this situation, tacking on the layline will result in a lot of time spent sailing in bad air. It may also force you to overstand in an effort to find clear air. Both scenarios will cost you boats. You can avoid this by tacking before the layline. The tricky part, however, is choosing exactly when to tack.

It’s likely that you, as well as the boats around you, are sailing towards the layline because it’s the correct way to go. Maybe you’re waiting for a shift or sailing toward a puff. If so, you may have to tack early to avoid the layline and stay in clear air. To avoid tacking any sooner than you need to, anticipate when the boats in front of you will tack. How early you need to tack depends on how many boats are ahead. You don’t want to give up any more than is necessary with regard to the shift or puff. Keep in mind that everyone else will be trying to stay in clear air as well.

International 505 champion Peter Alarie explains this concept by thinking of clear lanes as numbered in order of desirability. The lead boat is going to take lane No. 1. The number one lane may be right on the shift or on the layline. To keep its air clear, the second boat will take lane No. 2, to leeward of No. 1. The third boat will take No. 3 and so it goes down the line for all the boats that are close enough to affect your air. If you’re in fourth position, you can’t tack in lane No. 3. If you try, you’ll end up in bad air.

There’s often an opportunity to be the “vulture.” If you’re in fifth position and you see the fourth boat sail past lane No. 4, then it’s yours. The fourth boat will end up overstanding or sailing in bad air. If this is the case, you will most likely pass them on the next crossing even though you sacrificed some of the shift or puff.

Make sure you consider how much you’ll give up strategically and weigh it against the gains you’ll make by sailing in clear air. Occasionally it pays to spend some time in bad air in order to get to a good spot on the racecourse.

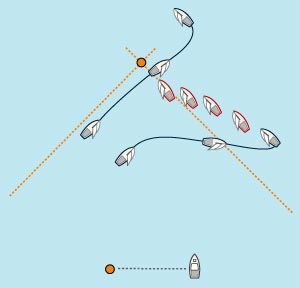

Just behind, approaching a short starboard layline

Imagine yourself behind a pack of boats, approaching a short layline. This is similar to the previous example except that you’re closer to the mark. When approaching the port layline, it’s usually best to tack out early any time you’re not leading, especially when you’re in a pack of boats.

Approaching a short starboard layline is a common scenario. If the group in front of you is tightly packed, consider overstanding. As the lead boats tack on the layline, boats approaching on port will be tempted to leebow rather than duck a long line of starboard tackers. A boat that successfully leebows outside the two-length zone may have to pinch in order to make the mark, forcing the boats to weather to also pinch. The result can be a large group of boats all sailing slowly towards the mark. An extreme case of this can result in a pile up at the weather mark.

In these cases, you can make a big gain by coming in above layline at full speed and sailing around the pack while your competitors luff each other at the mark. How much you need to overstand will depend on the boats in front of you. You may need to overstand slightly more than a boat ahead of you trying to do the same thing. There’s a point of diminishing returns. If a lot of boats in front of you overstand, you’ll have to overstand too much in order to have clear air. In this case, it’s better to slightly overstand and sail in bad air. Tacking below the pack should be avoided. If you’re close to the mark this is likely to force you to the port layline and ultimately present you with a wall of starboard tack boats on the layline.

Just ahead, on the port layline

If you must approach on or near the port layline, duck boats you cannot cross. If you can cross, make sure to delay your tack until you’re completely clear of the crowd.

Sometimes you can’t avoid approaching the mark on the port layline. If you’re not crossing boats on the starboard layline, you have to duck them to avoid fouling. If you’re crossing, be careful not to break Rules 13 or 18.3. Be sure to completely cross starboard-tack boats before you start your tack. You’ll probably round after the boat you crossed, but that’s better than doing a 720.

Just ahead, approaching a short starboard layline

If you’re ahead approaching a short starboard layline, you’re in good shape but not quite out of the woods. It’s important to tack right on the layline. By nailing the layline you force your competitors to either leebow—and risk not making the mark—or duck. Since you would much rather have your competitors duck, it’s good to give them a little encouragement.

If it looks as if they’re going to try a lee bow, bear off a little bit. One of two things will happen. A savvy competitor will realize that you’re about to force them to tack below layline, and decide to duck you. A less experienced sailor will be forced to tack sooner than expected and probably botch the lee bow. In this situation, you should be able to use the extra speed generated by footing to pinch up and make the mark. Be careful not to overdo it. You don’t want to foul (breaking Rule 16.2) and you still want to get around the mark without having to tack.

All of these situations call for a good deal of anticipation. Ask yourself, “what would I do if I were in their position?” If they behave as you anticipate, you’ll have had plenty of time to plan your move in response. If they do something you don’t expect, it means they’ve probably made a mistake. This means you’ll have an opportunity to take the better lane and make a gain before you round the weather mark.

GET TO THE ADVANTAGED SIDE OF THE COURSE

April 12, 2002, by Stuart Walker

Sailing World

When racing on short courses, it’s especially important to get to the advantage as soon as possible.

There Are Three Kinds Of Sailboat races—ones so short that the advantaged side doesn’t matter, ones so long that the advantages tend to even out (or other factors are equally or more important), and races of medium length in which getting to the advantaged side is paramount. On medium-length courses, which are typically set near shore, there’s usually an advantaged side. The first boat to reach the advantage usually wins, because after it does, there’s insufficient time remaining for anyone to catch up.

In big fleets sailing long courses, the best strategy is to start in the middle of the line, keep to the middle of the course, expect that any advantage to one side (unless extreme) will be reversed by some advantage to the other, presume that boatspeed will get you into the top 10 at the weather mark, and await the mistakes of your opponents.

In small fleets on short- to medium-length courses, the opposite is true. Here, the best approach is to start at the extremities of the line, head immediately toward the advantaged side, and realize that boatspeed is of little value unless you get to the advantage first.

One side is almost always advantaged, either because of a persistent shift, the onset and subsequent veering of a sea/lake breeze, the dominance of a particular phase of a series of oscillating shifts, by favorable current, stronger wind, or smaller waves. Before the start, the competitor must evaluate the conditions and decide, not whether, but which side is advantaged and then develop a plan to get to that side first.

Essentially, this means that you must start at one of the extremities of the line—to leeward of all other boats heading left when the left side is advantaged, or to windward of all other boats with the ability to be the first to tack to port when the right side is advantaged. However, such perfect starts require precise timing and positioning and all too often a small mistake results in being driven through or over. Alternatives are available.

What matters most is getting to the advantaged side of the course before your opponents, not necessarily getting off the line first. The first step at about one to one and a half minutes before the gun is to sail into a position, either beyond the advantaged end or to the advantaged side of the fleet, from which it can be observed as it organizes for its final approach. From such a position, it will quickly become evident to which end of the line most boats are headed and whether most of them will be early or late. Perhaps everyone will act in accordance with Yogi Berra’s presumption that “the place has become so crowded that no one goes there any more” or in light air will be unable to reach the desired end in time. Opportunities to make the perfect end start may then become evident and should be utilized.

There are two special circumstances in which this perusal will reveal such an opportunity: when the opposite end of the line is more upwind and will attract most of the fleet, and in strong current. A tack below the most leeward boat on the line when the right end of the line is more upwind, but the left side is advantaged or a position above the most windward boat on the line when the left end is more upwind, but the right side is advantaged is usually possible. In favorable current, seek the pin end from a position below the layline. In unfavorable current, approach the weather end from a barging position.

If the pin end is upwind and the left side of the course is advantaged, you should arrive at a location a few boat lengths beyond the pin and just below the extension of the line with about one minute to go. Try to be the last boat to come back on port, because if you’re not, you’ll be controlled by the one that is. From here, if the air is light and the fleet late, one may bear away on port, cross ahead, and tack in clear air to windward. If the fleet is on time or slightly late, you can cross below the pin with about 20 to 30 seconds remaining, tack under the leading starboard tacker, luff them if necessary (after completing your tack), and bear away to arrive at the pin with the gun. Vary the radius of your circular approach to the first starboard tacker so that at the tack’s completion you are bow to bow with them. If the fleet is early, you should bear away at high speed below the first few boats, find a hole, tack into it, and come up tight under the boat to windward.

Sometimes, if the pin end is heavily favored, boats will be tacking to port as soon as the gun fires. Your speed will permit you to slide through the hole that one of them creates and to emerge and tack in clear air to windward of boats hung up at the pin.

If the weather end is upwind and the right side of the course is advantaged, two alternatives to approaching on starboard and arriving at the committee boat on time are available. One is to approach from the port end (just as you would have done if the pin end were favored) but timed so that you arrive close to the weather end 20 to 30 seconds before the gun. From here, you should tack under the most leeward of the starboard tackers that is luffing up to the line. Come in late with speed; arriving early will permit some of the boats to windward to escape and go around you to leeward. After completing your tack, you should luff the most leeward boat, initiating a chain reaction that will affect most of the boats near the layline, and cause them to slow for fear of being shut out at the committee boat. You should then be the only boat in the vicinity that can bear away, get up to speed as the gun fires, and tack across the bows of those boats jammed astern and to windward.

The other, safer alternative is to make a late start, but do so right at the committee boat. At about one minute before the gun, take a position from which the fleet can be observed four to six boatlengths beyond the weather end and just below an extension of the line. If the fleet is late or excessively slowed by a lull or adverse current, you may be able to slide around the committee boat ahead of them. If they’re early, but moving quickly, the’ll have to bear away down the line, leaving you a hole at the gun. If they’re on time, you should delay and bear away so that you come in with speed right on the transom of the most windward boat. From this position, you should be able to prevent that leeward boat from tacking and be the first to tack yourself.

There are two caveats to remember, however: 1. If you come into your final approach late with speed, arrive early, and are forced to slow down, someone with speed will surely drive through, above, or below, and you’ll be in their dirty air all the way to the advantage and beyond. 2. Do not persist in your starting plan when another boat—beyond the port end or ready to barge—is attempting the same start. Keep to leeward and in control of them and be willing to go farther down the line or farther astern, if necessary, to avoid a catastrophe.

WORKING THE GATE

August 15, 2001 By Terry Hutchinson

For nearly a decade, leeward gates have been used to reduce congestion at the leeward mark. Before race committees started using gates, the tactics were simple if you were leading: Protect the inside. But today, gate tactics are more complicated than that. Now you have to ask yourself, “Which gate is closer? Which way do I want to go up the next beat? Where’s the traffic?”

Eight Ways To Gain At the Leeward Gate

1. Use a compass before the race to determine the favored gate mark.

2. Sail to the mark that appears bigger. It’s farther upwind and closer to you.

3. Round toward the correct side of the beat.

4. If in doubt, round the left gate. You’ll be on starboard when you tack to clear out.

5. If there’s traffic at the favored mark, consider the opposite mark.

6. Get the leader to question his choice of mark.

7. Be ready to change your choice of mark at the last moment.

8. At the mark, slow down to create space between you and the boat that rounded ahead.

If you’re the boat behind and you have the answers to these questions, you’ll be able to gain. If you choose the correct mark and work the traffic flowing through the gate, you’ll make up distance quickly.

How do you determine which gate is favored? Most race committees will set the gates early. Before the start, you should sail upwind to a position abreast of the gate. Line the marks up using a hand-bearing compass. If you’re doing this from the starboard or right-hand side of the marks and the bearing is 90 degrees, then you know the gates are square for a true wind of 180 degrees. Do a quick head-to-wind shot and determine the bias of the gate. As tactician, I write this down on the boat near my upwind numbers so I know which gate is favored compared to the true wind direction.

Sometimes the race committee won’t set the gate until after the start. This makes it harder to tell which gate is favored. Tactics and strategy aside, the best way to select the favored mark is to judge which mark appears to be bigger. If both marks are identical in dimension, the mark that appears to be bigger is closer. I like to ask my crew for their opinion to help confirm which gate looks favored. If both marks appear to be the same size, formulate your strategy for the upcoming beat.

Prioritizing the upwind leg

After you devise a game plan, decide which side of the gate will allow you to execute it. For example, if you want to go to the right side on the next beat, round the left gate mark. If you want to go left, round the right gate mark.

At the Acura SORC in Miami this year, the right side of the Farr 40 course was heavily favored. It was so favored that we spent the last mile of the beat on the starboard layline. Knowing this, for the next beat I wanted a position that would allow me to continue on port toward the favored right side, so I tried to get around the left-hand gate mark (looking downwind).

If you can’t decide which side of the beat is favored, round the left gate mark. When you need to tack after the rounding, you’re tacking onto starboard with right of way. Let’s say you round the left gate mark at the same time as a competitor rounds the right gate mark. Then you both tack; now you’re on starboard and they’re on port. If the gate was square to the wind, you’ll have right of way, and they’ll have to duck you. Then you’re a length ahead.

Also, if you have a bad rounding at the right-hand gate mark, you may not be able to tack if you’re pinned by boats that rounded behind you. They’re on starboard, and you’re tacking onto port.

So far, the process of choosing which mark to round might sound easy, but I’ve rarely been in the position where the decision’s so easy to make. When you’re in the thick of the race, traffic can change everything.

Tactics in traffic

Most people deal with traffic every day on their commute to work. I’ll bet some of them have shortcuts that are longer in miles but faster because there’s less traffic. The same principle holds true at the leeward gate.

The lead boat has the most options. But the trailing boat has plenty of choices as well. If you’re close astern there are a number of tricks you can use to get ahead. First, block the lead boat’s wind. If you’re successful, you may be able to force it into a slow rounding or away from the gate mark that you want to round.

Because the leader has so many options, it’s easy to make them doubt their decision if you make it appear you want to round the opposite mark. Sometimes they’ll be indecisive and switch marks at the last second just to stay ahead of you. Once they’ve committed, turn and head for the other mark.

If you’ve managed to confuse them, you may get the favored mark. Or you may force them to make a boathandling error. Even if you don’t, you’ll have clear air at the opposite mark. Follow the leader around the same mark only when it leads to a heavily favored side of the course. Make sure there’s enough space between the two boats so you don’t have to tack out immediately to clear your air.

In the Miami example, the right side of the beat was favored and everyone knew it. The fleet fought for the left gate mark and this made for a lot of extra distance sailed in dirty air at the bottom of the run. Boats lined up and waited their turn to round the gate mark. If you chose the right gate mark, instead, had a good rounding, a nice speed build, and then tacked, you’d often gain and still be headed toward the favored right side.

To be successful you must be able to change your choice of mark at the last second. This means your bow team needs to be ready for anything. You might tell them you’re thinking left-hand gate, but at six lengths out, if it’s obvious the left mark will be jammed with boats, the crew needs to be ready for a last-minute change of plan.

There are times when it pays to slow down. Let’s say you’ve fought hard for the inside position at the left gate mark so that you can go hard right up the beat. If there are boats that have rounded ahead of you, don’t ride their transoms. If you’re too close, you’ll be spit out, have to tack, and be heading toward the unfavored side of the course.

As soon as you get the inside overlap on your group, douse the spinnaker and start focusing on exiting the mark. The distance between your bow and the boat in front is crucial. If you can drop back a boat length and make a perfect tight rounding, you’ll be on a track toward the good side of the beat until most of the competition has been forced to clear out.

HOW TO CLAW BACK

Sailing World, December 15, 2000

By Scott Ikle

The difference between having a mid-fleet regatta and a great regatta is often the ability to come back after a big mistake. As much as you may try to sail flawlessly from the outset, if you’re human, you’re going to make a mistake at some point, in some race, somewhere in the regatta. Those who make the fewest mistakes win races. Those who can claw their way back from mistakes win regattas.

The most important skill may be attitude. If you can stay positive after a mistake, you’ll be better off than a competitor who allows their anger to blind them to the realities of the racecourse. Once you’ve made the mistake, acknowledge it, and let it go. Begin your comeback by taking a few deep breaths to relax and then start attacking the fleet. It’ll be important not to commit any more errors, so stay calm and alert.

After a poor start, your initial reaction may be to immediately tack for clean air. This will work well if the beat is square, giving you the ability to weave through the fleet and look for those all-important clear lanes. Tacking too soon after the start, however, may be dangerous; you may have a pack of boats on your hip that’ll be nearly impossible to get through. You may have to crash tack or duck the entire fleet. Avoid these potential pitfalls by being patient and tacking into an open lane.

Sometimes tacking is not the answer. If the first beat is heavily skewed, it may be better to stay put. In a major windshift, you may also want to stay on your original tack. Don’t forget your pre-race prep, if you determined before the start that you wanted to be on this tack, stick to your guns. Try footing off to increase your speed, watching for lanes as the boats ahead are forced to tack away. If you have to tack off, but plan to tack back quickly, consider tacking to weather of a starboard-tack boat rather than on their lee bow. You will then have a blocker protecting your lane.

Once things have settled down and you’re in a clear lane, start paying close attention to windshifts and the boats ahead. Once you’ve devised a windshift game plan, concentrate on sailing the beat well and out-sail the mid-fleet pack by sticking to basic tactics. Remember to be ahead and to leeward when leading boats to the next shift, and wave boats across when sailing on a lift. A common mistake that’s made by the mid-fleet pack is losing track of the weather mark; often the pack gets to the layline too quickly, stacks up in the corner, and overstands the mark. Often you hear of someone passing 40 boats in a race when coming from behind. They’ve likely made that big move by passing packs of boats that have all made the same mistake, not by knocking them off one at a time. Capitalize on the pack’s mistakes.

The best opportunity to pass the pack is at the weather mark. The pack will tend to stack up on the starboard layline, with all but the leader going slow in bad air. Sail well to leeward of the starboard layline parade. As boats are forced to tack out farther to clear their air, you can expect a hole to open up, which will allow you to sneak around the mark ahead of the pack.

Working a hole to leeward of the port layline isn’t the only way to pass boats at the weather mark. As much as we try to avoid overstanding, sometimes it can be advantageous. There could be a windshift at the mark, which slows the fleet as they approach. There could also be adverse current at the mark. Suddenly the fact that you’re overstanding means that you’re coming into the mark with pace, laying it, and looking smart as you pass the boats that had to tack twice or were pinching.

When clawing back on the first reach it’s critical to make up distance on the leaders. This is purely a function of using boatspeed to minimize distance on the leaders before the reach mark. Avoid boat-to-boat battles. Before you close in on the opponent ahead, decide whether to go high over the top, or to dive low, breaking through their wind shadow. Decide early and set yourself up with some space in order to pass them. In some classes, when the first reach is tight, the passing lane is always high. Go high early, avoid luffing matches, and blast over the pack. Only when the reach is broad, or there’s adverse current, should you consider sailing low on the first reach. And only go low if the pack is reaching high of the mark. This doesn’t mean sailing below the mark, but instead, sailing the fastest course straight to the next mark, delaying any passing maneuvers until you can begin to fight for the inside overlap.

On the second reach leg the dynamics are a little different. The inside overlap position is going to be fought by going high. Avoid the pack that’s fighting high and attack from the low road. The low-road move on the second reach is often an effective way to gain boats because you avoid the overlap battle and can sail faster on your own. As you approach the leeward mark, since you’ve sailed low at first, you’ll be able to reach up and pass the boats sailing low and slow into the mark.

The run is always a good leg for catching boats. It’s important to know how to round the weather mark. If you’re headed when rounding the mark, bear away and set. If you’re lifted, consider a jibe set. But there are other important considerations in determining which way to go on the run. It always comes back to what the wind is doing. If you believe that you’ll get a favorable shift, it’s often a good idea to sail away from the shift first so you can maximize your gain. However, if there’s more pressure coming, always sail for the pressure. If you can stay in phase and in pressure, you’ll always gain. As you near the leeward mark, always protect the inside position for the rounding. Remember, if you can’t get an inside overlap, slow up and round behind the pack, not on the outside. Rounding outside of the pack will put you in dirty air and reduce the number of lanes available to you.

An awareness of how the breeze has shifted as you’re rounding the leeward mark can be a key to making a comeback on the last beat. You want to get on the lifted tack right away and stay in phase. If you need to tack at the leeward mark, don’t just go around the mark and tack; sail for a few moments, and look for a lane. If you need to stay on the tack, pinch up around the mark, and almost shoot head to wind to get your bow above the centerline of the boat ahead, clear of their dirty air—the worst thing you can do is two quick clearing tacks. If you’re coming out of a crowded leeward mark rounding and there are few lanes to be had, your only recourse is to sail in phase, go the right way. The only way you’ll pass boats is to sail the shifts better than the next person, so let the others search endlessly for lanes, and let them gamble on the flyers. Just play the fleet, the wind, and make winning percentage moves.

Never give up on the last beat, and always finish at an end. You’ll be surprised how easy it is to pass boats near the finish line. Race towards the favored end of the finish line, and don’t sail any extra distance. If it’s close, shoot the line. You’ll be amazed how a properly executed shoot can win a finish.

Clawing back from a mistake means never making another mistake. The strategies and tactics don’t change, only your perception of the situation at hand. There’ll be dirty air, fewer lanes, and lots of traffic. Turn that into your advantage by waiting for other boats to make mistakes. Sail better than the rest of the fleet, stick to what works, and usually you’ll get back in the hunt.

SAIL LIKE A VETERAN TODAY

Sailing World, September 15, 2000

By Luther Carpenter

Years ago i was a young, hungry, youth sailor. I had great starts, flashy roll tacks, the ability to steer perfectly, and my parent’s Visa card. I could do anything.

But as I started competing around the world, I learned that desire and raw talent were not enough to win major regattas. There were always other guys, a few years older and a bit more serious, who consistently finished at the top of the fleet. I realized that their edge wasn’t talent or luck. It was experience.

In 1992, I coached at the Barcelona Olympics and witnessed a near perfect blend of youth and experience. Coaches Jonathan and Charlie McKee and team members Randy Smyth, Keith Notary, Mark Reynolds, Paul Foerster, Mike Gebhardt, Brian Ledbetter, and Hal Haenel had all been to the Olympics before—some had won medals—and they shared what they’d learned from their past experiences at the Games with our energetic and talented Olympic rookies. It was a powerful combination that resulted in medals in nine of 10 classes.

OK, you’re saying, I know experience is important. But what, aside from a suntan, rope burns, and wetsuit rashes, do you get from logging countless hours on the racecourse? And, once you know what’s so important about all this time on the water, how can those without experience quickly learn the veteran’s game? I found myself asking these questions while coaching in Europe this spring and assembled a list of veteran techniques, traits, and habits that would help some of our sailors earn their veteran wings.

1. Veterans have a top-notch boat, and are meticulous about maintenance. The centerboard fits perfectly, the lines and purchase systems are of the best quality and exactly the right length. Accurate marks are made on the boat for trim reproduction. The rudder/tiller system is tight and the extension is the right length. Veterans constantly improve their equipment. They study competitor’s boats and innovative ideas in other classes.

2. Veterans read the weather forecast. They think about the “big picture” for the current and following day. This gives them a sense of what to expect and how to distinguish between localized effects and weather system changes.

3. Veterans never sail past laylines.

4. Veterans assess the length of the starting line and the size of the fleet. Will there be enough room for everyone? How long will they be able to hold their lane? Having these questions answered before the start enables them to visualize the opening minutes of the race. Veterans also determine the favored side of the line and the course. They think about the length of the beat and how long they will sail on each tack. At the SPA Regatta in Holland this year, the Europe beats were long so we emphasized getting off the line clean, sailing in clear air without tacking early in the beat, and then returning to the center of the course.

5. Veterans know when to go for the big starts and when to back off and start more conservatively. Veterans track the fleet psyche. U.S. Sailing Team coach Gary Bodie used to encourage his college teams to stay away from the pin end during the opening race of a regatta. The fleet’s adrenaline is usually high at the beginning of events, and pin-end starts are risky. However, Bodie also told his teams to go for the pin after the lunch break, when the fleet was sleepy.

6. Veterans “beat the fleet” on local knowledge. In the first race of a series in normal conditions, they’re not afraid to use local knowledge. At SPA this year, the first day had a typical sea breeze, which we knew would favor the left side. Much of the fleet was hesitant to commit heavily to the left in the first race, so it was a great time for our sailors to leverage left and produce a big opening race.

7. Veterans use the time sailing to the racecourse to assess conditions, and determine what technique and setup will be fast. They compare present conditions with the forecast. They set themselves up for a changing wind scenario, so the gear change comes naturally, and without hesitation.

8. Veterans go after wind velocity. They believe in what they see. Veterans are not afraid to wing it on a side if they need to make a move, or see something good. Veterans are the first to react to big changes.

9. Veterans have perfect weather mark roundings, and they immediately execute their downwind game plan. They’re not afraid to stray from the pack for clear air. They’ve researched the wave angles and are the first to catch waves.

10. Veterans demand to pass boats. They’re never happy with status quo.

11. Veteran technique is smooth and fluid. They’re sensitive to helm pressure and respond with weight and sail trim.

12. Veterans focus on balance first, and then add kinetics. They feel the boat. Balance is most important; kinetics enhance the balance with extra power. If your kinetics are rough or don’t have flow, go easy and feel the boat.

13. Veterans are aware of sheet pressure on all sails. Pressure is everything. A perfectly trimmed sail is one that is pulling on the sheet the hardest.

14. Veterans have excellent leeward mark roundings. This is the gateway to passing boats on the second beat. They focus on execution.

15. Veterans avoid traffic. They know that groups of boats have less wind than single boats. If you find yourself alone, don’t rush to get back to the other boats.

16. Veterans have good reasons to tack. If they’re going fast in clear air, they keep going unless something changes (windshift, too leveraged, more wind).

17. Veterans rarely sail upwind in bad air. Everyone knows bad air costs you boatlengths; you don’t need to prove it.

18. Veterans sail with their heads out of the boat as much as possible. They always know where they are, and where the marks are. They rarely make a navigational error. Chris Nicholson, of Australia, won three 49er world championships by being better at watching the wind up the course, while everyone else focused on a more immediate view.

19. Veterans note wind trends during the race, and think about how they will affect upcoming legs. A big left shift on the second beat is going to tighten the top reach on a trapezoid course and favor reaching on the last downwind leg. Veterans set up the boat perfectly for these changes and open both offwind legs with a gain over those still assessing the leg.

20. After the finish, veterans drink plenty of water, reflect on the wind, think about rig changes, and get to the starting line so they can relax before the next race.

21. Veterans understand the importance of physical size and fitness. They sail boats that match their body types. They know the physical requirements of their class and are properly conditioned. They also can readily admit and act to improve upon or compensate for any weakness.

22. Veterans sail and practice in a quality manner more than their competition. It’s a simple fact: Time on the water with specific goals equals improvement.

WIN THE PIN WITH MATCH RACING MOVES

Sailing World, November 15, 2001

By Betsy Alison

If the pin is favored, many sailors will jockey for the perfect pin start. The ability to leg out on starboard below the fleet or to tack and cross the competition is an advantage worth fighting for. Of course, you may have to battle for it; rarely will a good fleet give you the pin end at the start. The trick to winning the pin is to control the situation and take charge of your own destiny. There are two match-racing moves that can help you win the pin, but you must make one critical decision: Do you lead the pack to the pin, or do you push them?

Leading to the pin

This maneuver is best executed with a port-tack approach to the line. In a typical starting scenario, the flow of boats will move counterclockwise between the race committee boat and the pin. If you want to lead the pack to the pin on starboard, it’s best to be the last boat on port and tack closely to leeward of the boat nearest to the pin. A port-tack approach allows you to see any available holes and how others are positioning for the start. Tacking tightly below the boat closest to the pin allows you to control the situation. From this position, you can prevent the boat above from moving towards the pin, and you can herd the pack in a windward position while protecting your hole to leeward. A critical element in making this work is the concept of “time and distance.”

In order to accurately position yourself to win the pin, you need to gauge how far away you are from that sweet spot, and exactly how long it will take you to get there. It’s important to spend some time in your pre-race preparation gathering this information. Being one or two seconds early can ruin your start, forcing you to jibe around into traffic. To properly execute this start, you must know three things: 1. How long it takes you to sail the length of the line. 2. How long it takes you to get from any stationary object in the water, a lobster pot or anchored spectator boat, back to the pin. 3. How long it takes you to tack and accelerate. The time to sail a given distance will vary with your sailing angle—reaching is faster than running or beating. And don’t forget to consider current set.

Once you’re in a lee bow “leading” position, your time and distance homework should pay off as you pick the moment to put your bow down towards the buoy, accelerate, and win the pin start. The biggest risk is a rogue boat coming in from astern attempting to snatch your hole while you’re herding the pack above. Keep a wary eye astern, and to discourage a rogue boat, put your bow down, ease your boom out, and close the distance with the pin layline. Make it obvious that the rogue will not be able to sail to leeward of you and still fetch the pin. In fighting off the rogue, however, make sure you don’t underestimate the time and distance required to reach the pin. In other words, don’t run out of room yourself.

1. To lead to the pin, approach on port and tack to leeward of the crowd

2. To push to the pin, get on the tail of the lead boat. Your goal is to overlap to leeward and luff them, or make them early.

The best times to lead back to the pin are: 1. In light air, because tacking angles are wider and you can accelerate more easily with no one under your bow. 2. When you have a large runway available to the pin. 3. If a pack of boats is crowding toward the pin. With everyone overlapped, it’s much easier to control the group.

Pushing to the pin

Pushing an opponent is another way to win the pin, but it requires a keener sense of time, distance, and layline position. Before the start, test the layline to get a feel for its position, and then sight through the pin for a marker on land—a shore sight. Check this layline reference several times to ensure that it’s accurate—wind shifts will cause it to change.

Pushing is most effective when you’re vying with one other boat for the pin. It’s more effective in stronger wind because it’s easier to accelerate and the ability of the lead boat to slow and stop is reduced. Pushing requires using the match racing technique of tailing another boat closely. The goal is to force the lead boat to use up its runway to the pin, forcing it to luff and slow prematurely. This should allow you to establish a leeward controlling position, or to pressure the lead boat into being early and jibing out.

When pushing the lead boat toward the pin, match their sail trim and angles in order to stay on their transom without gaining a weather overlap. As you push, the lead boat will probably fishtail back and forth, trying to slow its rate of progress toward the pin and attempting to “hook” your bow into a weather overlap. If you become trapped to windward, the lead boat has won. With luffing rights, the lead boat can control the action, slow its approach to the pin, and create a hole to leeward.

As the lead boat tries to hook you, your move is to bear away, cross their transom and overlap them to leeward with speed. If you can establish a substantial overlap to leeward early in this dance, you can then luff and stop the lead boat and control the approach to the pin. If the lead boat bears away before you get a solid overlap, you’ll soon fall astern in their dirty air.

Once astern, you have two choices: the first is to aim for the pin and continue sailing fast, forcing the lead boat to match your course to stay ahead. Alternatively, you can luff sharply if you’re running out of time or if the lead boat has sailed past the pin layline.

As the pusher, keep in mind that if you establish a leeward position from clear astern, you are required to assume your proper course after the start. If you have erred on time and distance, misjudged the layline to the pin, or trapped your bow to leeward with mere seconds to go, you’re in big trouble. At best, you’ll have a second row start; at worst, you may not fetch the pin.

Having a great start almost ensures that you’ll be in the top pack up the first beat. Confidence in your ability to handle the boat in tight quarters, hold position, generate and protect a hole below your bow, and accelerate at the proper time are vital to winning the pin. One match racing technique that helps is backing the jib hard to windward to swing the bow down and accelerate without a lot of rudder movement.

There is nothing more satisfying than winning the pin and having all the options open to you. Try these aggressive moves in smaller, less competitive fleets at first. Then try them against a more competitive pack. Slowly, your timing, boat handling, and confidence will improve. The pin will be yours whenever you want it.

San Francisco J/105 Fleet #1

San Francisco J/105 Fleet #1